Warholak Tire Service, 9411 McGraw, Detroit:

Generations of Family Service in West Side Detroit’s Polish Neighborhood

On McGraw just east of Wyoming Avenue, at the gateway to west side Detroit’s old Polish community, sits a family-owned business that still today represents everything the Polish immigrants stood for: hard work, trust, ethics, service, dedication, family values, fairness, charity, community. All those attributes live on in two brothers who operate and manage the business—all passed down by their ancestors who founded the business nearly five generations ago.

Mike Warholak, Jr., is a partner, with his brother Paul, at Warholak Tire Service, and he is filled with family memories and stories of the shop’s history. The Warholak family moved to the corner where the tire store is currently located in around 1926. At the time, the LaSalle Plant of General Motors, which later became DeSoto, then McGraw Glass, was located across the street. It was a time when the surrounding area was filled with large open fields. One of them, across the street from the store, was called Haggerty Field. It was during the early days of aviation, back in the 1920s, when air races were held there, and where Mike Sr. learned to fly.

Growing up, Mike, Paul, and their sister, Maria, were told they were of Russian heritage. But they learned that their ancestors had descended from a group of people who lived in the foothills of the Carpathian Mountains known as Carpatho-Rusyns or Ruthenians. A sub-grouping of those people was known as Lemkos. These people inhabit a stretch of the Carpathian Mountains known as Lemkivshchyna. In medieval Piast times, this area became part of Poland. In 1772, the Lemko province was made part of the Austrian province of Galicia. The area then became part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire until its dissolution in 1918, when the Lemko-Rusyn Republic declared its independence. But in 1920, the republic was incorporated into Poland. Mike describes his Lemko heritage as more cultural than geographic. From a religious perspective, he says that Lemkos are primarily Greek or Byzantine Catholics or of the Russian Orthodox faith.

Three of Mike’s grandparents came from Galicia. A maternal grandparent came from a village closer to Ukraine.

Mike’s grandfather Onufry, who was known as Fred, was born in 1884 and immigrated to America in approximately 1900 at around age 16. He spent some time in Pennsylvania, then moved to Cleveland and, ultimately, to Detroit. In Cleveland one of the things he did was manage a bar. He also met and married Terezia Gresko while in Cleveland. Terezia was from a village near Gorlice, in Galicia. Their wedding reception was at the Lemko Hall, which was featured in the movie The Deer Hunter. The ceremony featured in that movie was very similar to a Russian Orthodox ceremony.

Upon moving to Detroit with his bride, Fred performed a variety of jobs but was involved primarily in moving and demolishing houses. Terezia raised four sons and a daughter: Harry, Frank, Michael, Fred Jr., and Helen. There were three younger boys who died during the influenza epidemic of 1918-1919, as infants or small children. The family lived on Buchanan Street for a while and in a few other houses and then settled on Merwin. Directly alongside the tire store is the house that was built in 1930. The house still stands today.

Fred owned a Packard dump truck. In the days before the tire shop, Terezia would get up in the morning and pour some boiling water to heat the engine on cold days before Fred went out to crank it up. Jobs were designated according to age. The two older boys cleaned brick and the younger children straightened nails. Everything in the house was reclaimed. Today the house itself has been repurposed and is used for storage for the tire business.

In 1931, Fred built the front end of the shop as it stands, entirely from reclaimed materials. It has a tin ceiling in both the office and in the shop, which Fred installed. The story, as passed down by Mike Sr., is that all the materials were reclaimed from Detroit’s Corktown District. In 1929, the north side of Michigan Avenue was widened to accommodate the arrival of the streetcars. Mike Jr. speculates that the materials may have been derived from the Michigan Avenue renovation. Regardless of their origins, Fred obtained enough materials to build the house and then the shop the following year. Mike is sure that the Warholak siblings cleaned their share of brick and straightened their share of nails throughout those years.

Fred did hire some people, including two Ukrainian brothers, to do the actual construction. The brickwork on the house, which is 88 years old, is phenomenal. Above the picture window there is a tree designed into the brickwork. Ash was mixed into the mortar as a stabilizer. Fred did not pay the workers, but Terezia fed them three times a day. It took two and one-half or three weeks to do three or four days’ worth of work because the workers were getting fed so much.

Fred’s first contract with a gasoline supplier was with Sinclair Oil. Opening day was July 3, 1931, and Michael (Mike Sr.), his oldest brother Harry, Frank, and their younger brother Fred Jr., who was eight years old at the time, all went to work at the shop. Mike Sr. was not yet 11 years old. At that time, across the street from where the Ford-Wyoming Drive-In is today, there was a Mack truck facility, where truckers would park their trucks. The Warholak boys would run down Ford Road—when it was still all dirt—pick up the trucks, fill them up with fuel at the shop, and then drive them back to the facility. Fred Jr. was so small that he would sit on a box. The trucks at that time did not have power steering, and the steering wheels were huge.

The Warholaks were very protective of one another. At one point Mike Sr. had a paper route, and there was a man on his route who refused to pay him for months. So young Mike told his brothers about the rebellious customer. The brothers were probably between 16 and 18 years old at the time. They got together with a couple of their buddies and went over to the man’s house and, ahem, “collected” the money.

Later, instead of a paper route, Mike Sr. had a newspaper stand. One of the highlights of his life was when a big black Lincoln limousine pulled up to the curb in front of the stand, whose occupants wished to buy a paper. When the window rolled down, the fellows buying the paper were none other than Henry Ford and Thomas Edison, riding in the back seat of the car.

The three oldest boys and Helen all went to Chadsey High School. Fred Jr. attended Cass Tech, where he played trumpet. He also played in the U.S. Army Band. Frank and Harry also served their country, both in the Army Air Corps. Harry received Bronze Stars for distinguished and meritorious service. (Mike Sr. did not qualify for service.) The young men were really good mechanics, which stemmed from their father having grown up on the farm. As Mike Jr. puts it, when you’re left to your own devices, you learn how to fix things. Those people developed a way of looking at a problem and devising a way of resolving it. They knew how to use their mechanical and design skills.

Mike Jr. says that his dad could take a machine and, with no idea what it was, could figure out what was wrong with it. All the Warholak boys possessed that same attribute, which was invaluable throughout the years, as they all continued to work in the tire store along with their sister Helen—which brings us back to the air field across the street.

There were no mechanics on site at the air field, but fortunately there was a service station within walking distance. When the pilots had mechanical issues at the air field, they could walk over to the service station and get one of the Warholak boys and take him over to the air field to see if he could help with the planes. The boys were in their teens at the time. Thus, they developed an attraction to flight early on. As compensation for their efforts, the pilots would either pay the boys or take them out to fly. Consequently, Mike Sr. earned his pilot’s license in 1940 at age 21 from that air field.

Harry had served in England during World War II, and when he returned and went back to work at the tire store he said that he was making double the money in the Army as he was at the store. So he decided to leave and open up his own auto parts shop. Fred Jr., Frank, Mike, and Helen remained at the tire store. Fred Jr., Terezia, and Helen were still living in the house at the time.

Clara Ford, wife of Henry Ford, died on September 29, 1950, and she was laid in repose in the home she shared with her husband Henry Ford at Fair Lane in Dearborn. Terezia insisted on paying her respects to Mrs. Ford, in spite of her sons’ admonitions. Terezia was unyielding and hailed a cab, commanding the driver to take her to Fair Lane in Dearborn. Upon arriving there, she got out of the cab and walked up to the gate. When she was refused entry due to the viewing being private, Terezia, in her broken English, insisted that she be allowed in to pay her respects to Mrs. Ford. She was so insistent that she was finally given entry. She said her prayer and left.

Terezia, who was only about five feet tall, was so strong and so strong-willed that she once single-handedly fought off a bull in a field at a family gathering. She was a powerful woman before her time. In Mike Jr.’s words, “She was the straw that stirred the drink. She was the head of the family, the matriarch, the rock.” Terezia passed away in 1964.

Mike Jr. recalls that once a month or so, he, his brother and his sister would spend the night at their grandmother’s, in the house next to the shop. “We wanted to play with Grandma and Aunt Helen. Aunt Helen was single and in her thirties. She was a lot of fun. She always had a bottle of seltzer water and grape juice concentrate. As kids we used to mark our heights on the wall, and it’s still there, mine and all the cousins.”

In 1950, Fred Sr. passed away, leaving Fred Jr., Frank and Mike to run the business. A short time later, Frank decided he wanted to try something different, so Mike Jr. and Fred Jr. eventually bought out Frank. He returned to the shop at a later date for approximately 15 years. Afterwards, in the early to mid-1970s, he opened an auto parts store. In approximately 1985, Mike Jr. and his brother Paul bought out their Uncle Fred (Fred Jr.). The two brothers have been running the tire store together since that time.

Mike Jr. is now 63 years old, but he recalls going down to the store on a Saturday when he was 12 or 13 years old—just as his own father did—to work when there was a truck to unload, or “just to get out of Mom’s hair.” He is a graduate of Michigan State University and at one time thought he may attend law school. However, the tire store has become his calling, especially after working with his dad for so many years.

Mike Jr. went to work for the tire store because “that just felt like the right thing to do.” Mike says that they all got along pretty good—“as well as two brothers and a dad can for 10 hours a day.” He also felt a sense of belonging. He was baptized and attended church at Ss. Peter & Paul Russian Orthodox Church in Southwest Detroit. He grew up in Detroit and moved during his college years. His maternal Grandfather Opalak (who passed away in 1957) had a store right down the street on Cicotte and Dennis. The store closed in 1958 or 1959 following his grandfather’s death.

Mike Sr. passed away in 2009 at age 89. Most all of the family is buried in Woodmere Cemetery. The tradition goes on: Mike Jr.’s son is 25 years old and works at the store now as well. Mike explains that that’s the reason why Abick’s Bar is “so near and dear” to him. He says that he probably shot his first game of pool at Abick’s when he could barely see over the edge of the table. “Aunt Manya,” as he refers to the now-deceased former owner of the bar, was his brother Paul’s godmother, and her daughter Marie was Mike Jr.’s mother’s (Elizabeth Opalak’s) goddaughter. “They’re like another family,” he says of the Abicks.

“We would go to church on Sunday, get out at 11:30, and the bars wouldn’t open until noon. We would knock on the door and they would let us in as little kids. But only if we promised to be very quiet,” he recalls of the Abicks. He was at the bar every Sunday from the time he was born until he was 18 years old. “We used to come down here and go door-to-door Christmas caroling on Gilbert and Cicotte, and they would give us cookies and give our dads a shot,” he remembers.

When Mike Jr. was young, things were much different than they are today. Tire distributor “reps” would come into the store. B.F. Goodrich was one of the big distributors, and they manufactured PF Flyers sneakers. Knowing that Mike Sr. had three kids, every so often—approximately every six months—the company provided him with “incentives,” and he came home with boxes of brand new PF Flyers sneakers.

The shop has seen the brightest times and has survived through the hardest times. During the 1967 Detroit riots, Mike Jr. remembers his dad coming home for dinner and leaving to spend the night at the shop, equipped with shot guns.

Mike loves the business, but he has higher hopes for his son. In his opinion, there was a period of unprecedented growth in the city of Detroit when his grandfather, father and uncles were building up the business. Detroit was known as the Arsenal of Democracy. Everyone was doing really well. But he does not believe we will ever see that pace of growth again.

It doesn’t upset him, though, and he doesn’t blame anyone for it. He simply believes that that was a unique time in the history of Detroit and America. “After World War II, we had, virtually, all the manufacturing capacity in the entire world. We exported 50 percent of everything we made. A person could graduate high school at 16 years old and go over to the auto company and get a job,” he says. He doesn’t believe that will ever return.

Mike, and his brother have worked at the tire center six days a week for 38 years, and he feels the physical effects of that hard work.

Mike speculates that probably everyone in the west side Polish neighborhood bought their tires from Warholak at one point, throughout the years. He says that one of the significant things about being there for all those years is that a lot of people in the Polish community understand service. “Men in their family have owned a butcher shop, or have been a doctor or a baker. They know good service. They’re involved in what they’re doing. Family ties mean a lot. If your father or your grandfather shopped there . . . . We have families that have been there for six generations.”

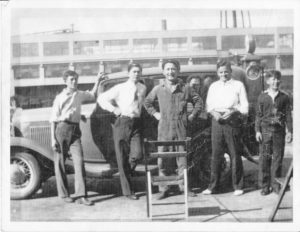

He says that every once in a while an old timer comes in who remembers his grandfather and his father. He’s sure that his grandfather worked extremely hard. But at the same time, he has photographs in the little breezeway between the house and the shop depicting his grandfather with a shot of whiskey and a deck of cards. It could have been a weekend when the photographs were taken, but his grandfather knew the value of making time for leisure along with working hard. Mike’s family still has some of the stringed instruments that his grandfather used to make.

He says that his grandfather made the business to take care of his family. Ironically, he created a situation in which his grandsons could still take care of his son. Mike Sr. had Alzheimer’s for the last 14 years of his life, and Paul and Mike Jr. would bring him to the shop daily to watch him during those years.

According to Mike, the shop’s current clientele is approximately 20 percent Middle Eastern, 20 percent African American, 20 percent Hispanic, 20 percent white, and 20 percent everyone else. The age group is anywhere from 17 to 90 years old. “Most of our business is referral. We try to instill a sense of trust. You can buy tires at a lot of places but you get people who send their wives or daughters or sons down. We aren’t out to gouge them, and the thing that bothers me the most is how a lot of auto-related services treat women. We feel really strongly about that. We treat all our customers the same way. That’s just the way we were brought up. Whether you’re wearing a $5,000 Armani suit or a hijab, we treat you the same way. That’s something my brother and I got from our father.”

“There’s a little bit of me that came from my great-great-great-grandfather or mother. That’s something I’d like to think: that some of the best traits are passed down. My father was the same way as my grandfather: generous to a fault. I genuinely love my customers. Our welcome sign says, ‘We treat you like family whether you like it or not.’ We’re just genuinely interested in what you’ve got going on. That’s because both my grandfathers instilled it.”

“People ask, ‘Why don’t you move out to the suburbs?’ People around here really own us. They expect us to be here. That would be a real hard thing to do. It would be hard to say, ‘I’m moving on to greener pastures and you’re on your own because I’m going to make more money.’”

Although it has managed to feed three generations of Warholaks, money is not the only thing that the Warholaks are about, and it is not what Warholak Tire is about. Mike recalls that his father told him that during the Depression farmers would come in from Ypsilanti or Pinckney to Western Farm Market, which was located on Michigan Avenue and 18th Street, and sometimes they did not sell enough to afford gasoline to make the return trip home. They would stop by the shop and Fred would buy some of the items they had, even if he didn’t need them, so that they had enough money to put fuel in their trucks and get back home.

Last year, Mike had an opportunity to go to Poland and visit the village where his grandfather was from. He visited the beautiful old wooden church in which is grandfather was baptized. Afterwards, he traveled north approximately 15 miles to the center of Lemko culture. A woman agreed to be his guide. He learned that his grandfather would have gone south approximately eight miles to where the market was. So Fred, his father, and their family members would load up the wagon with a mule or ox and sell their goods. And there were times when they came back and would not have sold anything.

And it dawned on Mike that this was what his grandfather was doing for those people who had traveled from Ypsilanti to Western Farm Market and were unable to make the trip back home: He would help them out so that they could get back to where they had come from.

Mike’s dad (Mike Sr.) was always an outdoorsman. Going to where his grandfather was from caused Mike to understand immediately: The place was a lot like Pennsylvania and upstate New York, with its rolling hills and loads of mature pines, the same sort of weather, and farmers in the field. In 1947, after the War, Stalin carried out Operation Vistula. The river runs through that part of Poland. They seized all the land of the Lemko people and dispersed them all to Siberia and other places because they were complicit with the Ukrainian underground. Thousands of Lemkos were murdered. In 1990, the Polish government reached out to the Lemko people specifically and stated that if they wanted to come back they would make their homes available again.

While visiting the Old Country, Mike saw some Warholaks in the cemetery in his grandfather’s village. About a mile away from their church there is a tire center on the side of the road. Mike stopped and gave the owner a Warholak T-shirt. The man said there were still Warholaks in town, as well as an auto parts store on the other side of town.

Editor’s Note: This history was taken from an interview with Mike Warholak, Jr., at Abick’s Bar (also listed as one of the Society’s Significant Sites), 3500 Gilbert St., Detroit, on June 7, 2018. It was also published in the August 2018 edition of the Society’s e-Newsletter. The WSDPAHS is extremely grateful to Mike for providing us with this invaluable history.